The development of prisons from the medieval dungeon to the modern penitentiary can be traced in the history of Downpatrick.

Before 1775, imprisonment was rarely used as a punishment for felony. For major crimes such as highway robbery, housebreaking, grand larceny and murder, the normal penalty was death, otherwise sentences were short. Prisons were more a method of confinement for debt and for those waiting for trial, execution ot transportation, than a place of punishment. By 1800, while hanging and transportation remained the major punisnments for serious crimes of violence, terms of imprisonment became more usual as punishment for petty felonies.

Although there was no legislation on prisons until the seventeenth century, many towns had provided themselves with prisons which were regulated according to local needs. Medieval Irish gaols were not purpose-built structures; castle-towers, gate-houses or cellars served. In Downpatrick, the building in the centre of the town known as "Castle Dorras", supposedly erected by John de Courcy in the twelfth century, was used as a gaol until 1746. In that year House of Correction, for minor offences, which stood in English Street on the site of the present "Courtside" restaurant, was converted into a gaol.

By the end of the eighteenth century there was need for a new gaol. There had been a serious fire in the insecure and badly maintained English Street gaol, resulting in the loss of six lives.

In the 1780's the prison reformer, John Howard, who had visited Downpatrick on his tour of inspection which exposed corruption and abuse in prisons throughout Britain, Ireland and continental Europe, stimulated the introduction of important measures to improve prison construction and conditions. In each gaol the Grand Jury was to enquire into the state of the gaol and if necessary enlarge it.

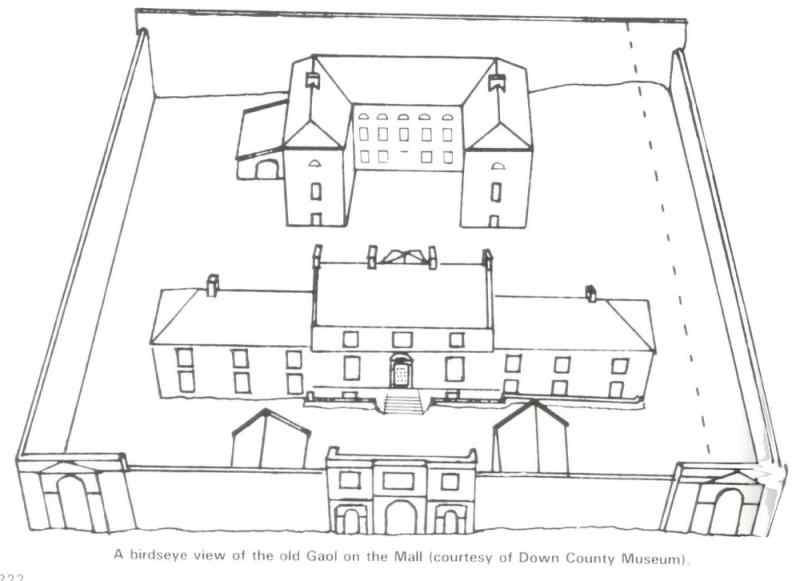

In 1789 the Grand Jury of County Down, the landlord dominated local government of the day, selected a site between the Courthouse and the Cathedral on the historic Hill of Down and appointed the Dublin Architect, Charles Lilly, to construct the new gaol. The Grand Jury directed that "the felons cells be divided in three storeys - the whole to be executed at £6000 expense to be raised off this county". The buildings, finished in 1796, were in use until a new gaol was completed in 1831. Used for many years as an Infantry Barracks they are now the home of the Down County Museum.

In 1789 the Grand Jury of County Down, the landlord dominated local government of the day, selected a site between the Courthouse and the Cathedral on the historic Hill of Down and appointed the Dublin Architect, Charles Lilly, to construct the new gaol. The Grand Jury directed that "the felons cells be divided in three storeys - the whole to be executed at £6000 expense to be raised off this county". The buildings, finished in 1796, were in use until a new gaol was completed in 1831. Used for many years as an Infantry Barracks they are now the home of the Down County Museum.

Life in gaol

During the eighteenth century some people had been shocked by the conditions prevailing in Irish prisons. Perhaps more significantly, many were frightened by the inefficient effect of the penal system in stemming the rising crime rates.

The inmates themselves often controlled the prisons with the strong exacting tribute from the weak. Male and female prisoners, those awaiting trial, those already convicted, debtors, the sick and the healthy were herded together in unhealthy surroundings. The reformers recommended that men and women prisoners be separated and put in clean cells; that there should be hard work, with pay, to encourage discipline; solitary confinement to allow lost souls to meditate on the terrible consequences of wrongdoing and the banning of alcohol. Much of this thinking was embodied in the 1786 Prisons Act and others which followed over the next forty years.

However, overcrowding made it impossible to implement separation of prisoners, especially in smaller prisons. The prison population was greatly increased by the custom of confining debtors in prisons intended for criminals. Prisoners awaiting transportation sometimes remained in prison for months or even years before being transferred to the convict ships. In addition the detention of prisoners until fees for release were paid, and a lack of short term accommodation for those who had committed only minor offences, caused further overcrowding. Furthermore, insane prisoners were confined in prison for lack of suitable institutions.

The gaol was not totally secure, and some prisoners asconded. See Escaped Prisoners. To be clear, it was James Hayes who was 5 feet 10 inches high, brown hair etc, not the horse.

The following is A Report on the State of the Gaol of the County Down at Downpatrick:-William Nevin, Esq. MD. Local Inspector, in 1818

Nothing very material has occured since the last annual Report; the number of prisoners has diminished, nor are any confined at present for crimes of great atrocity. The want of a separate gaol for convicts for transportation, is much felt, and also a convenient place for the confinement of approvers.

The melancholy effects of idleness are too apparent, in insolence and insubordination; could the prisoners be compelled to spend those hours in labour which they devote to recounting their past misconduct, and planning new schemes of annoying society, the happy effects would soon be felt and acknowledged.

From the sufferings of the prisoners of all descriptions under typhus fevers, the Grand Jury at last summer assizes presented a sum of money for the erection of a commodious infirmary for the reception of those labouring under acute and infectious diseases. "A number of Commissioners were appointed to receive plans and estimates; one has been approved of, and is nearly ready to be laid before his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant for his approbation."

Two hundred and thirty-one prisoners were committed here in the year of 1818; of them 87 were convicted, seven capitally, of whom one for murder was executed; the sentences of the remaining six were mercifully commuted to transportation for life, by order of the Lord Lieutenant.

One hundred and ninety-four persons were in said year committed for debt; 81 for debts above £20, 113 for debts under that sum, 19 were discharged by the Insolvent Act, 117 were discharged by their plaintiffs, eight were removed by habeas to the Four Courts Marshalsea, and 50 remained in gaol, 1 Jamuary 1919.

Abuses continued despite the appointment of salaried officials and the introduction of a system of inspection. In particular, rules and regulations were left to the discretion of gaolers and their assistants. The authority of the gaoler was exercised largely without supervision from the outside, a fact which reformers repeatedly highlighted as a major cause of prison abuse.

Abuses continued despite the appointment of salaried officials and the introduction of a system of inspection. In particular, rules and regulations were left to the discretion of gaolers and their assistants. The authority of the gaoler was exercised largely without supervision from the outside, a fact which reformers repeatedly highlighted as a major cause of prison abuse.

The following is a extract from "Travels in Ireland" by Thomas Reid MRCS, a naval surgeon, in 1822

About ten we arrived in Downpatrick, after breakfast visited the gaol, which is almost as bad as it is possible for a building of that sort to be. The construction renders classification, inspection and employment utterly impractical. Females of all descriptions, tried and untried, innocent and guilty, debtors and murderers, are all thrown together in one corrupting mass, and kept in a cell not near large enough. Sick or well there they must remain both night and day. There were twenty one thus confined when I saw it, one of whom had been sick for four months; it would not have surprised me had they all been sick. Over this cell is a place where a school is kept; it contained several spinning wheels, which is the only kind of industry in the prison.

The smell from some of the felon's cells was intolerably offensive. The prison is insecure; and so wretchedly constructed, that, although room is much wanting, there is one yard of which no use is made; it is covered with weeds and long grass. A school has also been established for the males; and this, was well as that for females, has been productive of great good, notwithstanding the disadvantages that operated against them. As hope is held out that "another prison will shortly be built or the old one enlarged", to point out any more defects would be unnecessary. I will merely take the liberty to offer my unbiased and disinterested opinion, that no enlargement or alteration can convert the present one into what a prison should be; the experience of making it even more tolerable would go a considerable way towards the building of one on a commodious plan, in which the morals of the persons confined would not be deteriorated as at present.

Some heed must have been taken of this since between 1824 and 1831 an extensive new gaol, permitting greater separation and closer supervision of a larger number of prisoners, was built close by. This "new gaol" was used until 1891 after Northern Ireland prisons were centralised. It was largely demolished in the 1930's. Its gatehouse can be seen at Down High School which now stands within its remaining walls.

This old Map of Downpatrick shows the position of all of the prisons over the centuries.

The exact origin of the use of transportation as a penal measure is obscure, but it seems to have developed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries from a need to avoid what were considered to be the destabilising influences of particular groups, such as the banishing of Irish Catholics to the West Indies during Cromwellian times. When, in the eighteenth century, the death penalty came to be regarded as too severe with respect to certain capital offences, transportation to North America - in the absence of an adequate alternative - became popular as a mitigation of such sentences.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries thousands of convicted prisoners from Britain and Ireland were punished with transportation to North America and the Caribbean. Transportation had the dual "advantage" of reducing the prison population at home and providing cheap labour for the new American colonies.

Legislation permitting transportation from Britain to New South Wales was first passed in 1784, and an equivalent Irish act followed in 1786 (26 Geo. 111 c 24). The British act did not name the destination, merely providing for transportation 'beyond the sea, either within His Majesty's dominions or elsewhere outside His Majesty's dominions'. The Irish statute provided for removal 'to some of His Majesty's plantations in America or to such other place out of Europe'. This difference between the two acts appears to have had the effect of enabling transportation to Australia from England to get under way in 1787, while there were difficulties with the Irish act. The passing of further legislation in 1790 (30 Geo. 111 c 32) designed 'to render the transportation of such felons and vagabonds more easy and effectual' rectified matters.

The American War of Independence stopped transportation to that continent and Australia was chosen for the establishment of a new series of convict settlements. Between 1788 and 1868 over 158,000 convicts were landed in Australia. Over 50,000 Irish men and women were transported directly from Ireland, beginning with the 148 convicts on board the merchantman "Queen", which sailed in April 1791. On board were six convicts from Co Down - William Burns, Thomas Flynn, Francis Little, James Marshall, James Randle and Thomas Williamson. The sentence of those transported varied from seven years for such crimes as thefts of clothing, food, animals or money, to life for political offences or as an alternative to the death penalty.

The history of transportation is filled with stories of brutality, neglect, starvation, disease and death. The number of prisoners embarked aboard the convict ships was substantially greater than the number landed at their destination. However, thousands survived this hazardous voyage, which coul;d take over 200 days, and eventually served their sentences to become free men and women in the new world of Australia, whose people have a greater proportion of Irish ancestry than those of any other country outside Ireland.

The following is the true story of a Downpatrick woman caught up in the system.

Ann Morrison was a "country servant" from Downpatrick, 33 years old with dark brown hair, hazel eyes and pock marked skin. She was convicted at the Down Assises in April 1820 for passing forged banknotes and sentenced to 14 years transportation to Australia. Ann had a child, Samuel, aged two or three and is destined to go to Australia with her. In the meantime he shared her cell as well as others. As was the case with many others, Ann and Samuel had to endure a prolonged spell in prison before being taken, via gaol in Dublin, to Cork, from where they sailed, in the ship John Bull on 23 July 1821, arriving in the colony of New South Wales five months later.

In 1823, in Australia, Ann married John Brown, en ex-convict from County Waterford, by then a free settler and farmer. She became known in the early history of the colony as "Mother Brown" presiding over a cross-roads hostelry in the developing settlement. She died in 1858. She had many descendants from her three children by John Brown. Her son, Samual, also left many descendants. On descendant, Mary McAlister, from New South Wales, told her story in Down County Museum in the 1990s.

More information about Anne can be found on the Morrison website, See Ann Morison in Australia

Acknowledgements:

Down County Museum

National Archives of Ireland